Interview with

Jane Hwang (Artist)

Face-to-face interview on 20. Dec. 2021

Email interview on 19. Jan. 2022

Interviewed by

Jeeyoung Lee

Translated by

Jane Hwang

Email interview on 19. Jan. 2022

Interviewed by

Jeeyoung Lee

Translated by

Jane Hwang

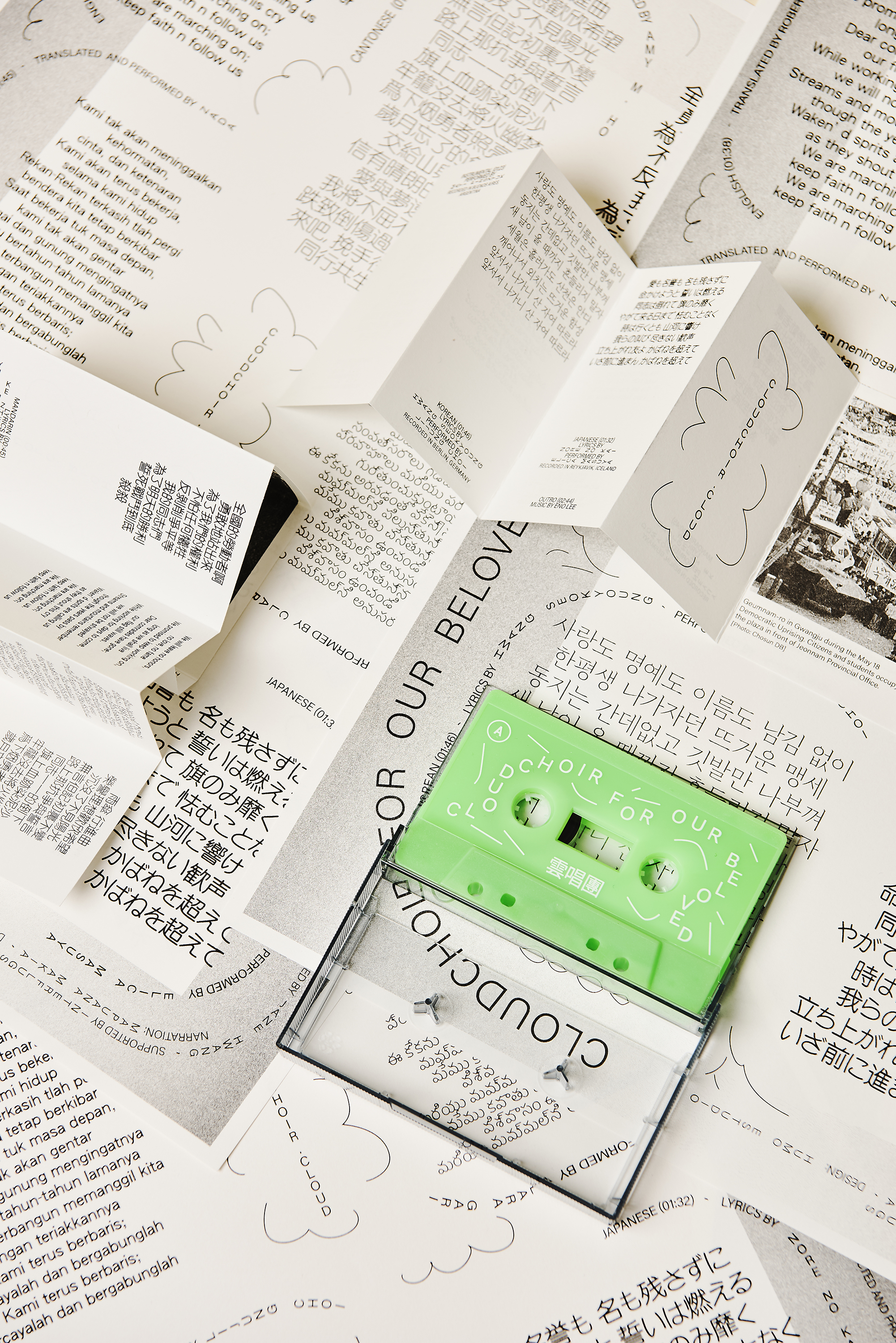

Cloudchoir for our Beloved (2020), Photo by Dongryoung Han

Jeeyong

Would you introduce yourself?

Jane

My name is Jane Hwang, and I am an artist based in Berlin and Seoul. In my practice, I work with time-based media to study the boundaries between history, the present, and the future from a narrative perspective. I am especially interested in interdisciplinary research exploring Korean history and the digitalization of commemorative culture. I am currently completing a master's program, “Art in Context” at the Berlin University of the Arts.

Jeeyoung

How did you start your project CloudChoir for our Beloved? What was your intention?

Jane

CloudChoir for our Beloved, 2020 is a collective project where a group of artists sing 'Marching for our Beloved' in different languages. The project actually started unintentionally, inspired by a moment. In Winter 2019, I shared the original sound file of 'Marching for our Beloved' with some multinational artists at a seminar. Although no historical background of the song was given (the song was recorded under the military regime's radar in Gwangju in 1982), listeners could assume the context of the tune and its urgency. Despite the fact that most listeners didn't speak Korean, some said that it reminded them of protest songs from their own history. We were immediately able to resonate with the music beyond words and culture, almost instinctively. It was this moment that prompted me to develop this project. Through CloudChoir for our Beloved, 2020, I aim to expand this observation to the act of group singing as a means to represent a solidarity among Asian artists that transcends language and region. The project was designed for collaboration from the beginning.

The project title obvious borrows from the song title ‘March for our Beloved.’ I added ‘CloudChoir’ to emphasize another major element: the recording and uploading of sound files from artists all over.

The final project includes a video and 50 20-minute long cassette tapes, which pays homage to the recording and distribution history of the original song. Cassette tapes are unique because the listener is unsure of what to expect before pressing the play button, unlike modern digital formats. The presentation of the content itself was also important. Cassette tapes reveal its content linearly. Listening to music from a cassette requires more effort; a listener will need to spend time fast forwarding or rewinding to fully experience a song. I intended to provoke time laborious work when listening to the cassette tape, creating an experience that demands higher level of listening.

![]()

![]() Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020, Compact cassette, 20 mins, 50 edition

Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020, Compact cassette, 20 mins, 50 edition

1-ch. video installation, 4:45, HD, sound 2020

Photo by Dongryoung Han

The project title obvious borrows from the song title ‘March for our Beloved.’ I added ‘CloudChoir’ to emphasize another major element: the recording and uploading of sound files from artists all over.

The final project includes a video and 50 20-minute long cassette tapes, which pays homage to the recording and distribution history of the original song. Cassette tapes are unique because the listener is unsure of what to expect before pressing the play button, unlike modern digital formats. The presentation of the content itself was also important. Cassette tapes reveal its content linearly. Listening to music from a cassette requires more effort; a listener will need to spend time fast forwarding or rewinding to fully experience a song. I intended to provoke time laborious work when listening to the cassette tape, creating an experience that demands higher level of listening.

Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020, Compact cassette, 20 mins, 50 edition

Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020, Compact cassette, 20 mins, 50 edition1-ch. video installation, 4:45, HD, sound 2020

Photo by Dongryoung Han

Jeeyong

Would you tell me more about your work process in detail?

Jane

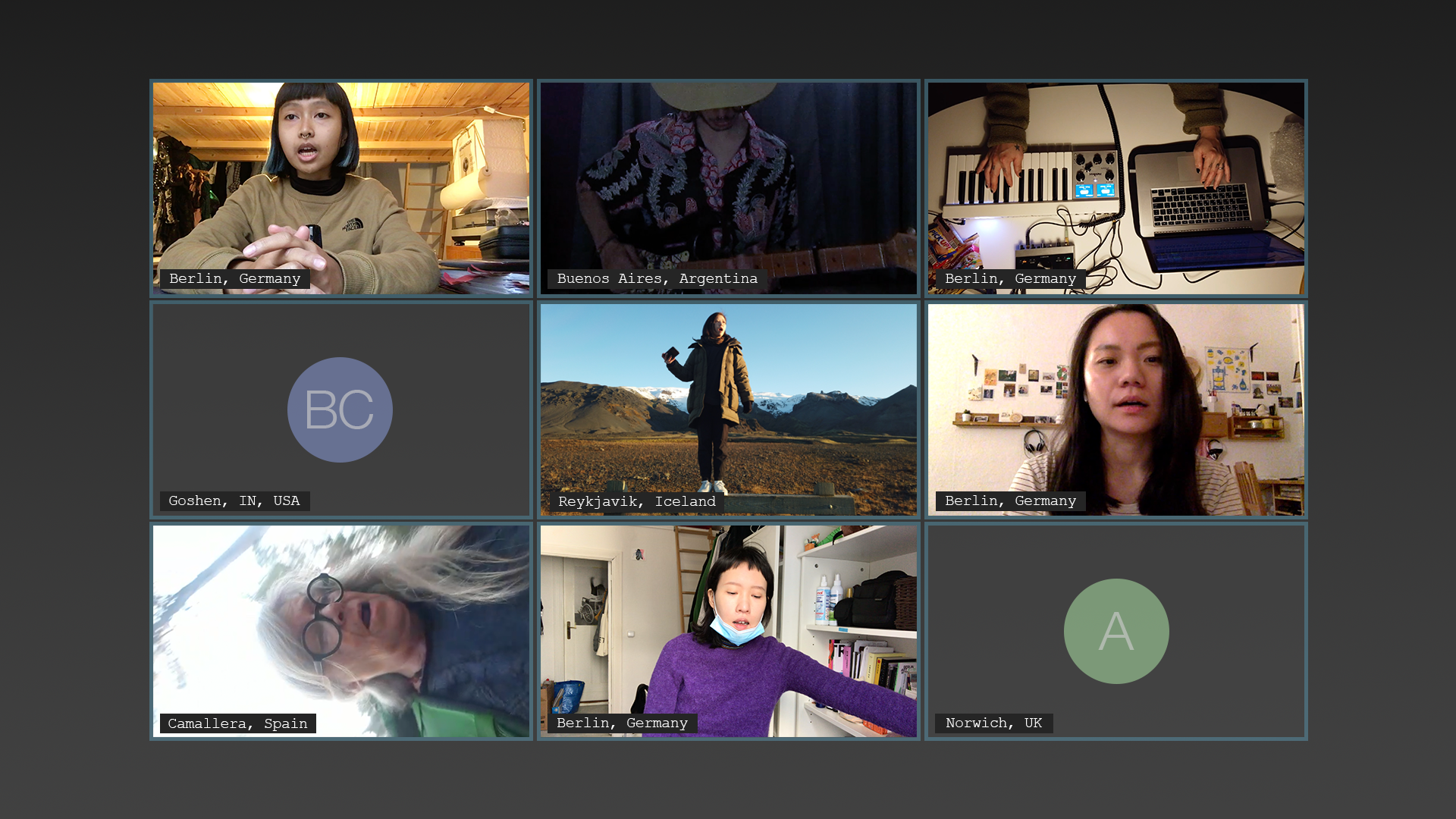

First, I limited participants to people who can read or speak one of the Asian languages and who support freedom and democracy in Asian countries. I posted a call on Facebook, through group emails, and by word of mouth. Finally, I gathered nine artists who would be willing to spend their time and efforts on this project. After identifying my group, I made a website to share all the information about the song and translated versions of the lyrics in different languages with the artists. Artists were responsible for confirming the translated lyrics that I found online. Three artists required translations that I was unable to obtain, so they were asked to translate lyrics into their desired language. Even in the logistical stages, people and their solidarity were at the core foundation of this project.

Participating artists were asked to sing the song in their own safe space, record their performance and upload the file. They were welcome to stay anonymous if they wanted: using voice and face filters or recording audio-only. A young Indian artist, who translated the song into Telugu, felt unsafe uploading the materials, so her collaborating partner from Spain decided to shoot the footage and record the song alone.

One Argentinian musician sent me an email saying that he found out about this project by chance and connected with it, but was disappointed he couldn't participate because didn't speak an Asian language. He asked me if he could join in, recording the song with his most confident language: music. He eventually sent me a video of himself playing a guitar arrangement of the song. An Asian-American artist bravely recorded a song in Cantonese with a trembling voice despite her non-fluent Cantonese skills. The final compilation video is 4 minutes and 45 seconds of minimally edited footage to maintain the original quality of the artists' recordings as much as possible.

I put together packages of cassette tapes and posters. For the cassettes, I attached the original audio files one after the other without editing and added narrations at the beginning and end. In the end, it was a 20-minute long experience. In terms of visuals, I wanted the packaging to look like that of an experimental independent label. So, I deliberately removed historical information about the project, which could possibly overwhelm viewers. Nevertheless, I tried to include some essential background explanations and old photos of Gwangju to the cassette tape sleeve. Still, my fellow artist in charge of the design insisted on leaving only one image of May 18th. Eventually, it was a clever decision to minimize the context to direct the listener to concentrate on the song's lyrics. In the end, 50 cassette tapes and 100 posters were produced. I sent each artist worldwide two copies of tapes and posters, hoping that they would further distribute one copy to whomever they wanted and keep one for themselves. All went to plan except for one envelope addressed to Buenos Aires that was lost during transit. Even then, after a new shipment, the product arrived safe in the artists' hands.

![Video Still Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020 1-ch. video installation, 4:45, HD]() Video Still, Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020

1-ch. video installation, 4:45, HD

Video Still, Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020

1-ch. video installation, 4:45, HD

Participating artists were asked to sing the song in their own safe space, record their performance and upload the file. They were welcome to stay anonymous if they wanted: using voice and face filters or recording audio-only. A young Indian artist, who translated the song into Telugu, felt unsafe uploading the materials, so her collaborating partner from Spain decided to shoot the footage and record the song alone.

One Argentinian musician sent me an email saying that he found out about this project by chance and connected with it, but was disappointed he couldn't participate because didn't speak an Asian language. He asked me if he could join in, recording the song with his most confident language: music. He eventually sent me a video of himself playing a guitar arrangement of the song. An Asian-American artist bravely recorded a song in Cantonese with a trembling voice despite her non-fluent Cantonese skills. The final compilation video is 4 minutes and 45 seconds of minimally edited footage to maintain the original quality of the artists' recordings as much as possible.

I put together packages of cassette tapes and posters. For the cassettes, I attached the original audio files one after the other without editing and added narrations at the beginning and end. In the end, it was a 20-minute long experience. In terms of visuals, I wanted the packaging to look like that of an experimental independent label. So, I deliberately removed historical information about the project, which could possibly overwhelm viewers. Nevertheless, I tried to include some essential background explanations and old photos of Gwangju to the cassette tape sleeve. Still, my fellow artist in charge of the design insisted on leaving only one image of May 18th. Eventually, it was a clever decision to minimize the context to direct the listener to concentrate on the song's lyrics. In the end, 50 cassette tapes and 100 posters were produced. I sent each artist worldwide two copies of tapes and posters, hoping that they would further distribute one copy to whomever they wanted and keep one for themselves. All went to plan except for one envelope addressed to Buenos Aires that was lost during transit. Even then, after a new shipment, the product arrived safe in the artists' hands.

Video Still, Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020

1-ch. video installation, 4:45, HD

Video Still, Cloudchoir for our Beloved, 2020

1-ch. video installation, 4:45, HD

Jeeyong

Were there any difficulties when working on this project?

Jane

The project still has some unanswered questions in terms of the participant diversity. According to the record, 'March for our Beloved' was also widely sung in Khmer, Burmese, and Thai, but these renditions are not included in this project. Through multiple Facebook posts and open calls, I attempted to recruit artists speaking these languages. In addition to this, I contacted dozens of voice-over artists on Fiverr, a platform that allows you to connect with and hire professionals for your project. Most of them showed interest in my request, so I shared details of the project and told them that they would remain anonymous. However, they all declined my proposition without clear reasoning. Some even said they were unwilling to participate in political matters even with compensation. In the moment, it was embarrassing, but I felt even more ashamed by my lack of action afterwards. I should have been more mindful about the current political landscape across Asia and employed a more sensitive approach when recruiting participants rather than simply relying on social media. In the process, I realized that it is not the individual artists' but the institutions' responsibility to promote such projects and recruit participants.

Contacting the institution and requesting cooperation was also challenging. I contacted an organization related to May 18th to ask for support. My initial idea was to pay an artist fee for those translated the song. They requested more details, so I sent them a project description and a sponsorship request. I have never heard from them ever since. Despite this, the project moved forward. Fortunately, the student organization within the Berlin University of the Arts was willing to support the material costs for the project. I believe that artistic discourses around May 18th is possible only when institutions support the production phase of each project before the exhibition phase.

Another difficulty I came across was the lack of archival material. On The May 18th Memorial Foundation's website, there is an independent Korean webpage for 'March for our Beloved.' However, their English website doesn't offer the same information. The same happens on the 5.18 Archives website- information asymmetry between the Korean and English webpages. 'March for our Beloved' was introduced and translated into several Asian languages and sung by the locals voluntarily. However, there wasn't any official record published, so I had to rely on Internet research, which may be inaccurate. One could say that this restriction opened doors for creativity.

Contacting the institution and requesting cooperation was also challenging. I contacted an organization related to May 18th to ask for support. My initial idea was to pay an artist fee for those translated the song. They requested more details, so I sent them a project description and a sponsorship request. I have never heard from them ever since. Despite this, the project moved forward. Fortunately, the student organization within the Berlin University of the Arts was willing to support the material costs for the project. I believe that artistic discourses around May 18th is possible only when institutions support the production phase of each project before the exhibition phase.

Another difficulty I came across was the lack of archival material. On The May 18th Memorial Foundation's website, there is an independent Korean webpage for 'March for our Beloved.' However, their English website doesn't offer the same information. The same happens on the 5.18 Archives website- information asymmetry between the Korean and English webpages. 'March for our Beloved' was introduced and translated into several Asian languages and sung by the locals voluntarily. However, there wasn't any official record published, so I had to rely on Internet research, which may be inaccurate. One could say that this restriction opened doors for creativity.

Jeeyong

How would you like to develop this project further? What kind of support would you require?

Jane

I would build upon the aforementioned issues and further develop this project. It will be an interesting archive if more languages are added to the second or the third albums. Also, Asia has a myriad of ancient and extinct languages. 'March for our Beloved' could be a medium for preserving endangered Asian languages. Just as the lyric of 'March for our Beloved' was translated to reflect the contemporary issues of different countries through time, the song can always be revised according to contemporary contexts and events. For that, institutional support should be the basis beyond the individual artist's approach. In addition to recruiting participants, we should create a safe space for them to express themselves freely. Participants' effort for translations, revision, and rewriting should also be compensated. If researchers could document and expand the archives through the process, it would allow the representativeness and influence of the song to flourish, which will then continually produce a new context and sustain its longevity over time.

Jeeyong

Do you have any other May 18th-related projects in your mind?

Jane

If I were to further develop this theme, I would continue researching resistance noises. For example, we can hear songs, shouting or slogans, and unpleasant sounds in the student movement- ranting and noises. In this case, then, sometimes rather than a well-made piece of music, a bursting shout or an incomprehensible cry of rage could represent the era. Considering this, it would be an exciting project to look into historical patterns in noises of resistance movements in different cultures- noises that have not been officially recorded such as music or slogans, i.e., dissonances that must be resolved.* On another note, the resistance of the current young generation could be represented by memes or gifs rather than sounds.

* I came across Fred Moten's book <Black and Blur> while developing this project, and here, Moten quoted Charles Rosen, an American pianist, when referring to dissonance. Rosen argues that dissonance is any musical sound that must be resolved, and it is not the human ear or nervous system that decides what dissonance is because consonance is determined at a given historical moment by the prevailing musical style.

* I came across Fred Moten's book <Black and Blur> while developing this project, and here, Moten quoted Charles Rosen, an American pianist, when referring to dissonance. Rosen argues that dissonance is any musical sound that must be resolved, and it is not the human ear or nervous system that decides what dissonance is because consonance is determined at a given historical moment by the prevailing musical style.

Jeeyong

Death has been your primary interest, and why is that? Could you introduce other ongoing or planned projects about this theme?

Jane

The underlying theme of my work is death and unresolved historical events. It is hard to say which comes first or even how to accurately determine a causal relationship between them. The boundary between two extremes, life and death, always interests me. What might be considered dead, like someone who can no longer talk is always, for me, a site of wonder and curiosity. I am currently working on a project about the civilian massacre during the Korean War in South Korea. This project was born from pondering how we can remember anonymous victims who were forced to be forgotten. I started the research in 2019, and it is now in production. Luckily, the research part of this project is funded by the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, which allowed me to invest a reasonable amount of time and effort into the research. During this process, I tried to suffuse my contemporary experience with the historical experience itself—to fill a gap between victims and a narrator, myself— seeking to integrate these ghostly memories into my own. The project will be realised as an interactive website as my own interpretation of the contemporaneity of commemorative culture.

Jeeyoung

Please tell me more about other projects that you are working on.

Jane

Besides these projects, I am envisioning a media where artists and art critics interact in writing. Multiple years of living in Europe taught me the necessity of solidarity among non-Western individuals. Decolonization discourses tend to be initiated mainly around reconciliation between the Western society, the perpetrator, and the non-Western society, the victim of colonialism. In contrast, solidarity among non-Western societies, each sharing memories of oppression, seems remarkably lacking. So, I thought that writing could intermediate transnational understandings and heal these oppressed societies. In fact, for me, text is the medium through which I can encounter a community most intimately. My registration as an individual publisher is currently in the process of being approved. My goal is to publish one magazine and one book each year in which artists and critics from non-Western countries introduce articles within the theme of 'decolonization.' In addition to publishing, a writer-in-residence program is also in the works. Both are still in the early stages, and I hope to develop a detailed approach this year.